-

Inside insyt’s colorful world: Mi Casa, Su Casa

APRIL 2024 || Rapper/ producer insyt’s debut album Mi Casa, Su Casa is an invitation into his wildly colorful, insightful, and deeply personal world. Nevertheless, his journey in creating it was far from straightforward.

It may be that the most important characteristic of a great artist is courage. Rick Rubin once wrote that “creativity is a fundamental aspect of being human…it’s for all of us.” But, while we all may be endowed with the ability to create, only few of us have the rare ability—the courage—to share the deeply personal. Courageous artists subvert the comfort of privacy in the service of creating great art that resonates on a fundamentally human level. Only this kind of art forces us, as spectators, to look inward. And, thus, it’s this courageously authentic kind of art that serves a greater purpose.

Fortunately, rising rapper/producer insyt is courageous. His self proclaimed guiding principle: “what’s mine is yours.”

Beyond the sophisticated, soulful production, insyt’s debut album Mi Casa, Su Casa is exactly as stated—an invitation into the artist’s wildly colorful, insightful, and deeply personal world. In it, he weaves together strings of honest self-assessment, reflections on his own shortcomings, and, ultimately, invites the listener on the deeply intimate story of his personal growth over the last year.

Nevertheless, considering the multiple EPs, tens of thousands of listeners on Spotify and Soundcloud, and half a decade’s worth of music experience under his belt, insyt’s journey in creating Mi Casa, Su Casa was far from straightforward. In making this debut album, insyt endured some of the most difficult moments of his life thus far.

“I feel the need to be honest about this stuff” insyt says. “Sharing it points me in the direction of being able to let it all go. Releasing the record and releasing the story helps me move on from the events that inform the music.”

“How to Draw a Circle” Directed by Genesis Dacayanan

Around this time last year, insyt was holding onto a completely different, original version of his debut album. After having planned to release the project last summer, a painful convergence of events including an ongoing battle against depression, the end of a years-long relationship, and the loss of a hard-drive storing the original project, forced insyt to reconsider the entire endeavour.

“It was an entirely different project,” insyt reflected on the original album. “It was a little more upbeat…I wasn’t digging in as much.” While the project may have been rose-colored, the artist had been struggling for months in a battle against depression that caused him to completely recede from life. He remembers this time in the early months of last year as some of the most difficult moments he’s endured. “It was dark. Like being stuck in a hole. Being in a place where people are trying to give you ladders to get out and you’re just like ‘no.’”

Around this time, the artist began dealing with the end of a years-long relationship—a circumstance that he recounts made him spiral even deeper into his depressive state. “Once the validation [I was getting] from the relationship was taken away,” he recounted, “It was more about me needing outward validation that kept me in the place of depression, instead of trying to fix myself.” It was this grief that would, more than anything else, shake the artist to his core and eventually serve as the focal point of today’s album.

So when losing the original project in the summer of 2023 put the final nail in the coffin of a months-long struggle, insyt knew he needed to come to terms with himself and seek self-care through his music. “It wasn’t really up to me,” he mentioned, “life kind of cornered me into addressing parts of myself that I didn’t like. Whether that’s insecurity or just not dealing with my shit. Not being there for myself.”

Ultimately, when asked about the loss of the original album, insyt claims it was completely out of his control, but completely necessary. “This [current] album happened because I needed the relief. I had to write these songs, so it wasn’t completely up to me.” The artist looks back on the original version of this album as inauthentic and lacking a critical examination of his circumstances at the time. Unlike the original, the album we hear today is strikingly authentic and unforgivingly critical, encapsulating months of grieving and overcoming his breakup and depression through self-assessment, gratitude, and mindfulness. The album is brimming with wisdom, not only on personal growth, but cultural and political commentary in usual insyt style.

insyt’s musical style is generally rooted in 90s hip-hop tradition. Like many before him, he’s a genuine crate-digger who loves to flip soul classics, but adds his own eclectic, even impressionistic, flair as one does when they’ve explored every capability of the SP-404. Sonically, Mi Casa, Su Casa is a mosaic of curated soul samples whose sweeping strings and melancholic vocal lines are delivered in relatively stripped-down production.

insyt describes the album as relatively simple sonically, the product of his desire to eagerly throw together a track and rap openly in real-time. As such, many tracks are drumless and droning, serving as a canvas for his lyrical musings. All in all, when it comes to production simple shouldn’t be mistaken for uninspired. Each sample and sound is purposefully used to reflect and amplify a message, such as “Black Andromeda’s” longing vocal line “the sun will come out tomorrow.”

“This album,” insyt mentioned, “is really like a four chapter book, based on the seasons. It’s my first time writing music in every season.” The first chapter, written late in the summer, just a month-or-so into grieving the end of his relationship, follows insyt as he comes to grips with all that has surpassed in the preceding months.

In this part, which includes the songs “Venus and Serena,” “Dharma,” “Joker Card,” and “Black Andromeda,” the artist’s tone can best be described as optimistic grief. He’s attempting to move forward, but you can hear his apprehension. And, as listeners, we’re left wondering whether he even believes himself. When asked about the first section of the album insyt jokes, “it’s hard for me to listen to those songs.”

One of these late summer tracks, recent single “Venus and Serena,” provides a lot of context for the emotional content of the album. The song is set against a light-hearted, swinging sample featuring an angelic harp and the repetitive line “your my summer, my winter, fall, and spring.” It has all the makings of a love song. In some ways it is, but as the artist struggles to overcome the grief of his former love, it’s inundated with contradiction. Determined statements of moving forward collide with whimsical daydreams about love in this detailed look into the mind of a grieving man. But, growth isn’t linear, moving on takes time, and insyt addresses this directly in one of the most expressive lines in the song, “you a cloud that’s in the bright sky/ moving through my thoughts so imma wave when you pass by.”

As listeners fall deeper into the album, they follow insyt through time, gleaning a different lesson or theme from every song along the way. “Dharma” is mantric, conveying a sense of fatigue as the artist experiences the burden of honesty. “Joker Card” is an apology. “Black Andromeda” is an anthem about using music to move through hard times. But, each listener will ultimately have to decide for themselves.

The last stage of grief is acceptance and the last stage of this album is no different. “Things get better around Once Upon a Time,” insyt said. Indeed, the doubtful prayers that we hear in the beginning of the album in songs like “Joker Card” (“I reckon there’s good days ahead, but I think of the old ones and laugh”) are answered in the later stages of the album in songs like “Once Upon a Time” (“Needed patience, guess I needed time”). These songs, written in the winter of last year paint a picture of the artist as someone who has endured the worst, but is now thankful for every experience—good and bad. In “Highly Favored,” insyt repeats “I’m thankful for the feelings that I poured in. Thankful for when freedom got distorted. Thankful for the frigidness of heartbreak. Grateful for the limits that I dug in and I broke through.”

There is an almost cathartic experience as the album comes to a close. If you’ve listened closely, you will have endured a full gamut of emotion. In seeing insyt’s success in finding a sense of peace, you yourself feel renewed (and relieved). In the best way possible, it doesn’t feel like you’ve spent 30 minutes with insyt, you feel like you’ve spent years with him.

When asked what the main takeaway is from this project, insyt says “my persistence, perseverance, continuously striving to make stuff and never trying to make music that I feel like is coming from the same place.”

“The key to that is living life,” he continued. “The artistic endeavour is in letting time pass, understanding, and putting that into the music. Music helps me. Music is kind of an anthem for understanding. Sometimes what I’m saying in the song isn’t what I’m feeling at that moment, but what I want to feel. I make it like an affirmation. It’s a mantra.” Insyt sees his poetic abilities as ways to encapsulate his feelings and therefore be able to approach them, saying “vocabulary, itself, allows you to understand things because it bridges the gap between ideas and understanding.”

And for the listener, particularly those who have been in similarly difficult circumstances, insyt hopes they are reassured by watching his long battle overcoming grief. “Seasons pass. Seasons change. And things aren’t going to feel the same way forever.”

insyt’s debut album Mi Casa, Su Casa will be released everywhere April 12th. You can listen to the recent single “Venus and Serena” today on spotify and soundcloud. How to Draw a Circle, the companion music video for Mi Casa, Su Casa is available today on YouTube and is embedded in the article above.

-

The Good Problems of Solar Energy

APR 2022 || The success of solar energy is revealing new problems for policy makers. Can we save solar modules from the land-fill and avoid a possible waste crisis?

Over the last two decades, solar generation has become the fastest growing energy source in the world. In the United States, this growth is largely driven by state and federal legislation intended to ramp up solar module production and deployment. Indeed, the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) states that, “Roughly half of the growth in U.S. renewable energy generation since the beginning of the 2000s can be attributed to state renewable energy requirements.”

As of 2022, over 30 states mandate renewable energy production through Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) and nine states have solar carve-outs which specifically prioritize solar generation. Just last year, for example, Virginia passed the Clean Economy Act which requires the state’s two largest utilities to produce energy from 100% renewable sources by 2045. Since 2018, many of these RPS bills have been amended to expand renewable energy production goals.

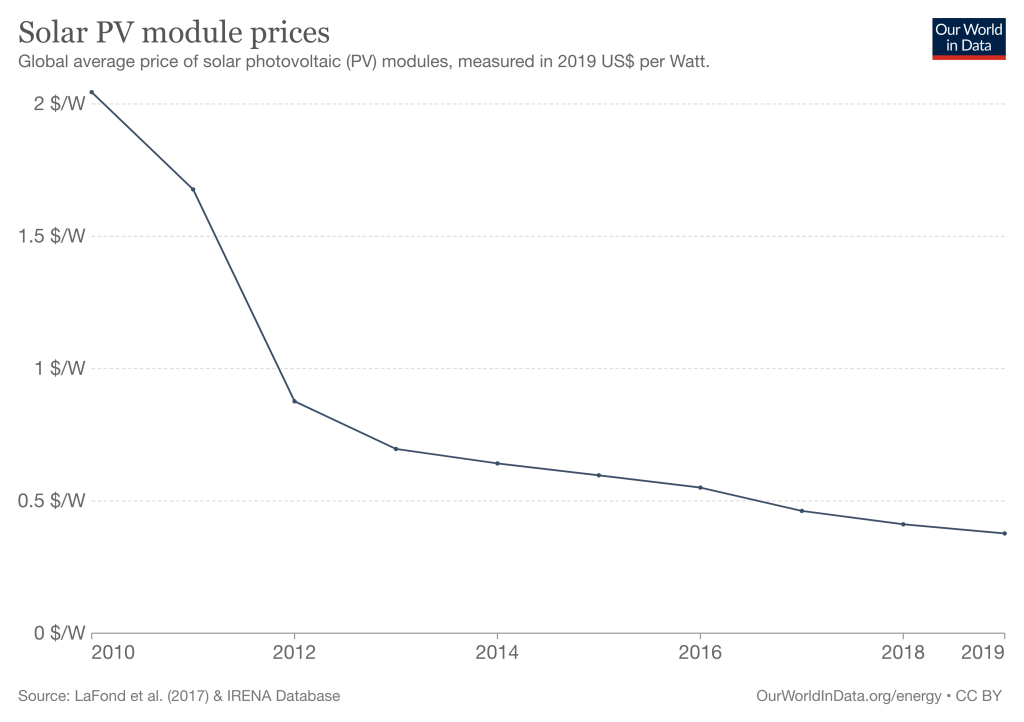

These pieces of legislation are packed with financial incentives such as Solar Renewable Energy Certificate (SREC) markets, tax credits, and net-metering options for consumers. As such, solar has become an increasingly compelling investment opportunity for consumers and solar developing firms alike. This increased demand is reflected in the consistent increases in affordability for solar modules. In the nine years from 2010 to 2019, the cost of a solar module decreased 1.66USD per watt.

The decreasing costs of solar technology means that firms specializing in solar development are lowering their input costs and seeing increased returns on their investments. Consumers, too, are benefitting from the mass deployment of solar modules because electricity prices are decreasing with the increases in solar capacity. From 2010 to 2020, the cost of energy from commercial solar generation dropped 90%. The United States Department of Energy stated that by 2030 solar energy is projected to cost “$0.03 per kilowatt-hour” and “be among the least expensive options for new power generation…below the cost of most fossil fuel-powered generators.”

Solar module deployment is running wild. We find ourselves in an energy landscape where solar development firms are fervently investing in solar projects and consumers are increasingly likely to reap the benefits of low (or non-existent) construction fees, low-electricity prices, and net-metering options—not to mention the intrinsic satisfaction of weaning from fossil fuels.

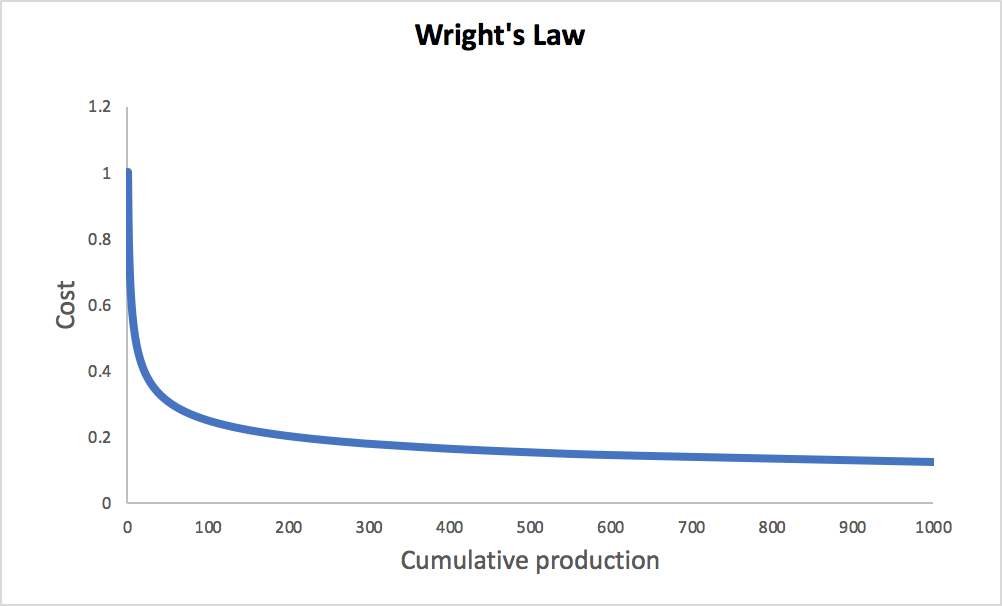

Rampant growth of solar capacity is ultimately the product of Wright’s Law—a framework that illustrates the exponential growth of technology. When solar modules were first created, they were developed by the government specifically for use in remote energy generation on satellites. Solar module production at that time was extremely costly and, subsequently, production was few. Though, as new uses for solar energy were developed and solar began to be seen as a terrestrial solution for greenhouse gas emission, production responded to the demand. With standardization of production processes and decreasing input costs, solar module prices began to fall.

This is a positive feedback cycle. Nevertheless, for this cycle to begin, there needs to be a catalyst in the form of an investment. In the case of solar, this was the legislation that created incentives for firms to invest in photovoltaic modules. Renewable Production Standards, tax credits, net-metering, SRECS, and many other policy mechanisms have been the wind under solar’s wings.

The frenzy doesn’t appear like it’s stopping anytime soon, either. As costs of solar energy are projected to continue falling, demand for solar is only likely to increase. Not to mention, in 2022 the federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC) will provide a 26% discount to anyone seeking to install residential solar modules. The U.S. Energy Information Administration states that “solar power and batteries account for 60% of the planned new U.S. electrical generation capacity.”

The ball is rolling for solar energy as we continue deploying record-breaking capacities. This production goes to show that state and federal legislation targeted at increasing solar capacity are working. The future is literally and figuratively bright for solar.

We Now Face the Good Problems of Solar Energy—Policy’s next problem is recycling millions of expired solar panels.

The last decade’s massive roll-out of solar technology is the reflection of a collective anxiety about the ongoing environmental crisis. We seek to throw-out fossil fuels because they are non-renewable, creating a by-product called CO2 which poses a major externality on the environment through climate change—a sliver of scientific knowledge that is known, and increasingly accepted, by absolutely everyone. Solar is alluring because it is renewable, posing no obvious environmental threat like greenhouse gasses. To many, renewable energy holds the promise of an idealistic, closed-loop economy where no waste is generated, products are built to last, and humans have a mutualistic relationship with the natural world.

Nevertheless, no source of “renewable energy” is completely renewable. Solar panels, like everything else, must succumb to the laws of Thermodynamics and depreciate. When a solar panel is no longer in operation, what’s left behind is a hunk of silicon, plastic, and silver that—as of now—we throw into a landfill. One major mistake when assessing the cleanliness of a technology is only considering its environmental impact while it’s in use. Environmental impacts should consider the entire life cycle—that means the impacts of making the technology and the impact it makes after its use. While the active time of solar panels is extremely beneficial, the production process and end-of-life stages of solar technology tell a different story.

Producing solar panels is a generally wasteful process. Manufacturing the technology requires machining holes through silicon wafers, creating a by-product called “kerf” which is a mix of highly-valuable, ultra-pure silicon and sawing fluid. Because extracting the silicon from the mixture is extremely expensive, solar manufacturers often consider it waste. According to the French start-up ROSI, “with the current solar capacity (115 GW worldwide), the photovoltaic module production is creating about 200,000 tons [$1.5 billion] of photovoltaic-grade silicon “waste” through kerf.” Ideally, the silicon that accumulates as kerf could be reintegrated into the production processes, but no manufacturers are doing this at the moment.

No manufacturers seem to have solved the end-of-life (EoL) dilemma of expired solar modules, either. As of now, only 10% of solar panels are recycled. Because the average lifespan of a solar panel is only around 30 years, the millions of solar modules deployed over the last two decades are set to come offline and into a landfill in the next decade. After that there is an unprecedented pipeline of expired solar technology to come as a product of our current era of deployment. By 2050, $2 billion worth of materials from solar panels are set to be dismounted and we have no large-scale end-of-life solution to account for it.

Ultimately, the wastefulness of the solar industry will pose a major externality on society. By discarding billions of dollars worth of ultra-pure materials, we are declining the opportunity to reduce natural resource extraction—a process that can be extremely threatening to local communities and will require an exorbitant amount of fossil fuels. Discarded solar panels cause additional environmental threats because they contain heavy metals such as cadmium and lead. Not to mention, the United States is already facing a waste crisis, as landfill space continues to dwindle at a remarkable rate.

Businesses, too, are losing out on billions of dollars of input materials and operating in a model that doesn’t maximize their long term profitability. The major material and monetary waste of the solar industry is the skeleton in the closet of what would otherwise be an incredible start to the sustainable energy infrastructure.

Hidden in this precarious dilemma, though, is an opportunity to recoup billions of dollars worth of materials and create a sustainable solar industry. Solar developers and policymakers know that solar modules only last a few decades and they know we have no way of dealing with them. The standard contract for solar developers—the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA)—usually stipulates a 25 to 30 year contract term for this very reason.

What are we waiting for?

Recycling solar panels requires processes that are still developing and are currently not cost effective on a commercial scale. Each module is like a sandwich with a plastic shell that allows for sunlight to pass through, but protects its complex amalgamation of silicon and silver components from the elements. The complex construction of the modules makes deconstructing them very difficult. Start-ups such as ROSI and Veolia are developing processes to recycle solar panels through various processes. The current, most popular method is creating a “glass cullet” (a mixture of ground up silicon, plastic, and glass) which is sold as a construction material. Unfortunately, glass cullet is cheap—selling for around $3 a panel—making it an unprofitable end-of-life solution for solar developers.

A more profitable solution would be removing and reselling the valuable internal components such as silicon and silver threading. While ROSI has begun using an innovative chemical-bath process to retrieve these materials, they and many other start-ups are still in preliminary stages of development. Ultimately, solar recycling processes and technology are still in the infant stages of Wright’s Law—low production at high marginal costs. Solar developing firms cannot reasonably be expected to recycle in a profitable way at this point in time.

Policymakers haven’t drafted very much legislation on the issue either—and their uncertainty about recycling technology is very much reflected in recently proposed policies. While there are no federal regulations driving the industry, many states have created commissions to investigate and make recommendations on end-of-life options for solar. Last year, three bills were proposed in California, Hawaii, and Rhode Island proposing best practices for solar recycling. The Hawaii bill considers adopting a fee for the disposal of solar modules into landfills—a financial incentive that could stimulate the industry. If passed, these bills would join a patchwork of legislation in Washington, New Jersey, and North Carolina. Many of the state investigations will generate guidelines by this summer, but none have made firm resolutions about requiring specific recycling standards any time soon. It seems as though policymakers know solar recycling will be an issue, but don’t know how—or if—they should deal with it.

The absence of policy around solar recycling makes sense. Up until very recently, no policymakers would consider a bill that would raise the marginal cost of producing solar. The goal is and has been making solar energy as attractive as possible. And, obviously, the process of establishing a renewable energy infrastructure begins with a large-scale rollout of solar technology. At some point, though, financial incentives targeted specifically at growing solar energy will end. Indeed, questions about the advantages of certain solar incentives are beginning to arise. In California, legislators are beginning to roll-back certain rooftop solar incentives because they believe it causes unequal electricity price increases for households that aren’t equipped with solar. Others are warning of residential solar incentives being withdrawn in the next 5 years.

When the policymakers are comfortable pulling the brakes on incentives targeted at stimulating mass solar deployment, their focus needs to turn to creating necessary support systems for the renewable energy infrastructure. Namely, developing policies with incentives to stimulate technological growth in the solar module recycling industry. This may mean implementing fees to discard solar panels in landfills as is being considered in Hawaii.

Because the technology and process of recycling is so costly, the industry needs to be stimulated by policy in the same way that the government incentives for solar production stimulated production of those technologies—thus increasing demand, production, and subsequently prices. As stated before a technology cannot scale unless there is an initial investment that begins the price reduction process explained by Wright’s Law. After a certain amount of growth in the industry, choosing to recycle solar panels—and recoup the millions of dollars worth of usable resources—may eventually be financially feasible, and even beneficial, for solar developers. Sustainable business is no longer an oxymoron. With the right incentives, businesses will elect to recycle so they can maximize their profitability—just as they now race to generate solar energy.

Obviously, there is no malevolence in deploying solar energy modules. These are the considerations of an adolescent period in renewable energy. Rapid deployment of solar technology is important, but it’s not the only consideration that must be made. If we want a truly sustainable energy infrastructure, we need to look at the big picture—we need to think in the long run. Regulatory bodies need to be thinking of policies to stimulate end-of-life solutions for solar energy. This is the path towards a closed-loop, genuinely sustainable energy infrastructure.

References

“Op-Ed: Sorry, Rooftop Solar Supporters, California Incentives Really Do Punish the Poor.” Los Angeles Times, 28 Mar. 2022, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2022-03-28/solar-rooftop-net-energy-metering-incentives-california-public-utilities-commission-cpuc-gavin-newsom.

Kerf Recycling | ROSI. https://www.rosi-solar.com/kerf-recycling/. Accessed 8 Apr. 2022.

Prieto-Sandoval, Vanessa, et al. “Towards a Consensus on the Circular Economy.” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 179, Apr. 2018, pp. 605–15. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.224.

“Real Estate Company Partners with Safari Energy to Develop Solar Portfolio.” Solar Power World, 22 Nov. 2021, https://www.solarpowerworldonline.com/2021/11/real-estate-company-partners-with-safari-energy-to-develop-solar-portfolio/.

“ROSI Solar – Towards Circular Economy in the Photovoltaic Industry.” ROSI, https://www.rosi-solar.com/. Accessed 4 Apr. 2022.

Sihvonen, Siru, and Tuomas Ritola. “Conceptualizing ReX for Aggregating End-of-Life Strategies in Product Development.” Procedia CIRP, vol. 29, Jan. 2015, pp. 639–44.

ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2015.01.026.

“Solar Panels Are a Pain to Recycle. These Companies Are Trying to Fix That.” MIT Technology Review, https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/08/19/1032215/solar-panels-recycling/. Accessed 4 Apr. 2022.

“Solar PV Module Prices.” Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/solar-pv-prices. Accessed 4 Apr. 2022.

State Renewable Portfolio Standards and Goals. https://www.ncsl.org/research/energy/renewable-portfolio-standards.aspx. Accessed 5 Apr. 2022.

“Time Is Running Out: The U.S. Landfill Capacity Crisis > SWEEP.” SWEEP, 4 May 2018, https://sweepstandard.org/time-is-running-out-the-u-s-landfill-capacity-crisis/. -

Disempowerment, Abuse, and Rigged Markets

NOV. 2020 ||

What’s the story behind your cup of coffee? Like most commodities produced in a globalized world, the answer to this question isn’t simple.

For many of us, coffee is a fundamental ingredient in our lives. It is responsible for our productivity, millions of jobs globally, billions of dollars in capital, and has kindled a complex global infrastructure to keep a steady stream of caffeine pouring into the world’s developed nations. While coffee-drinkers may trust the cute, green “fair-trade” labels on their coffee cups, the real story of coffee—and the people who are trying to change it for the better—is completely hidden from consumers. For years, the coffee industry has been in crisis mode as millions of farmers struggle to make subsistence income and climate change hampers production, while the developed world turns a blind-eye. The real story of coffee is about, “disempowerment, abuse, and rigged markets.”

Dean Cycon, the founder of Dean’s Beans Organic Coffee Company, is a person committed to fundamental change in the coffee industry. A self-proclaimed “seeker of knowledge, truth, and wisdom,” Dean is a pioneer in sustainable development who sees business as an opportunity to “seek a better understanding of the dynamics of everything from racism, to ecological justice, to interpersonal and intercultural dynamics.” After a career in indigenous rights and environmental law, Dean began the first international non-profit in coffee called Coffee Kids before creating Dean’s Beans in 1993. And since its inception, his company has been an experiment to determine whether a business that puts human values before corporate values can be successful—and it has.

Dean understands the coffee industry like no other. In his 30 year-long career, he has witnessed the evolution of coffee production from every angle and has developed a clear understanding of how the current system is failing its millions of farmers. Last year, Enveritas, a sustainability non-profit, determined that 71% of the world’s coffee farmers live in extreme poverty. Like us, the quality of life for a farmer is largely dependent on income, environmental conditions, and accessibility to basic social systems such as literacy and health programs. But two important factors are trapping coffee farmers in poverty: pricing and climate.

The income of a farmer is determined by what he is paid for a pound of coffee that he produces. Theoretically, when the coffee yields are lower, the price paid for coffee should increase because of scarcity in the market and vice-versa. This is called supply and demand, but it is not the way the coffee industry operates. The price of coffee, instead, is determined by the “C-price,” a speculative value determined by the London and New York boards of trade. In this model, private investment groups arbitrarily bet on the future price of coffee, which causes volatility in the income for a farmer. Farmers may produce the same bag of coffee every day, but still experience radical income fluctuations because of individuals sitting in a board room thousands of miles away.

The coffee crisis is also an environmental crisis. Scientists predict that up to 60% of coffee-producing land will be completely unusable by 2060. Predicted increases in climate may additionally account for the loss of 72% of tree biodiversity in coffee growing regions in the future. Most importantly, coffee is now becoming increasingly at-risk for fungal disease such as Coffee Rust, which drastically reduces yields and income for farmers. In fact, coffee growing regions will bear most of the burden of food and water insecurity into the future. And this doesn’t account for the self-imposed loss of biodiversity accounted for by monoculture and pesticide use.

The coffee industry is in crisis and millions of households are at risk. In a conversation with Dean Cycon, we discuss the deeply rooted problems in the industry and open the door to discussion about the hidden world of coffee.

Alfonsi, W. M. V., Koga-Vicente, A., Pinto, H. S., Alfonsi, E. L., Sr., Coltri, P. P., Zullo, J., Jr., Patricio, F. R., Avila, A. M. H. D., & Gonçalves, R. R. D. V. (2016). Climate change impacts on coffee rust disease. AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, 51. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2016AGUFMGC51A1133A

CARTO. (n.d.). Map of the Month: Bringing Smallholder Coffee Farmers out of Poverty. Retrieved December 10, 2020, from https://carto.com/blog/enveritas-coffee-poverty-visualization/

de Sousa, K., van Zonneveld, M., Holmgren, M., Kindt, R., & Ordoñez, J. C. (2019). The future of coffee and cocoa agroforestry in a warmer Mesoamerica. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 8828. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45491-7

Waller, J. M. (1982). Coffee rust—Epidemiology and control. Crop Protection, 1(4), 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-2194(82)90022-9