APR 2022 || The success of solar energy is revealing new problems for policy makers. Can we save solar modules from the land-fill and avoid a possible waste crisis?

Over the last two decades, solar generation has become the fastest growing energy source in the world. In the United States, this growth is largely driven by state and federal legislation intended to ramp up solar module production and deployment. Indeed, the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) states that, “Roughly half of the growth in U.S. renewable energy generation since the beginning of the 2000s can be attributed to state renewable energy requirements.”

As of 2022, over 30 states mandate renewable energy production through Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) and nine states have solar carve-outs which specifically prioritize solar generation. Just last year, for example, Virginia passed the Clean Economy Act which requires the state’s two largest utilities to produce energy from 100% renewable sources by 2045. Since 2018, many of these RPS bills have been amended to expand renewable energy production goals.

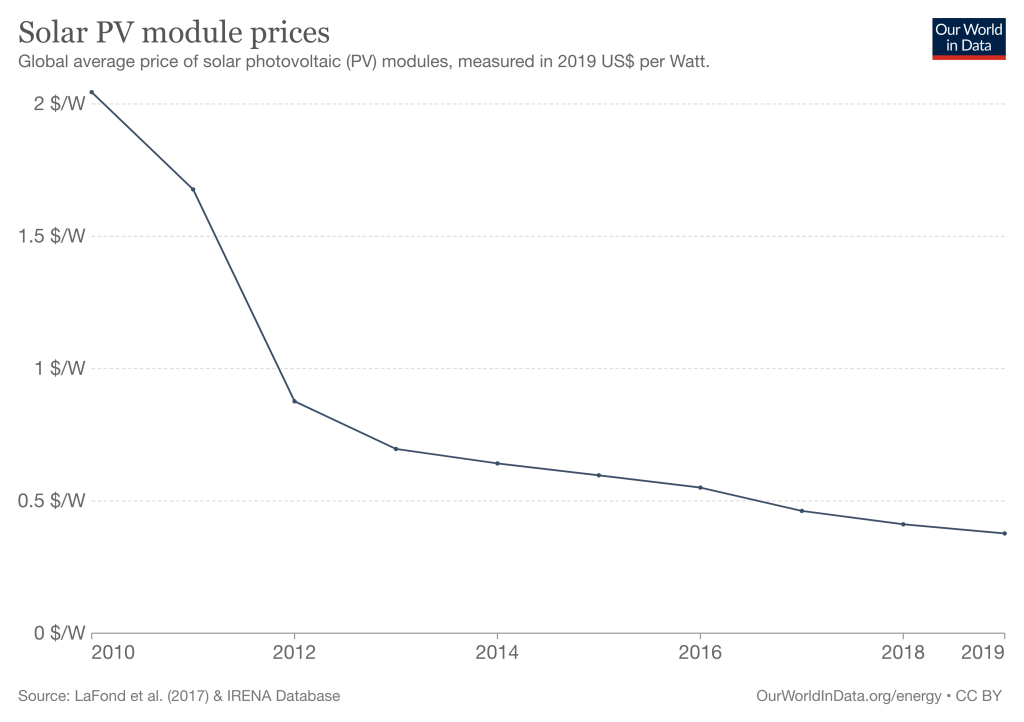

These pieces of legislation are packed with financial incentives such as Solar Renewable Energy Certificate (SREC) markets, tax credits, and net-metering options for consumers. As such, solar has become an increasingly compelling investment opportunity for consumers and solar developing firms alike. This increased demand is reflected in the consistent increases in affordability for solar modules. In the nine years from 2010 to 2019, the cost of a solar module decreased 1.66USD per watt.

The decreasing costs of solar technology means that firms specializing in solar development are lowering their input costs and seeing increased returns on their investments. Consumers, too, are benefitting from the mass deployment of solar modules because electricity prices are decreasing with the increases in solar capacity. From 2010 to 2020, the cost of energy from commercial solar generation dropped 90%. The United States Department of Energy stated that by 2030 solar energy is projected to cost “$0.03 per kilowatt-hour” and “be among the least expensive options for new power generation…below the cost of most fossil fuel-powered generators.”

Solar module deployment is running wild. We find ourselves in an energy landscape where solar development firms are fervently investing in solar projects and consumers are increasingly likely to reap the benefits of low (or non-existent) construction fees, low-electricity prices, and net-metering options—not to mention the intrinsic satisfaction of weaning from fossil fuels.

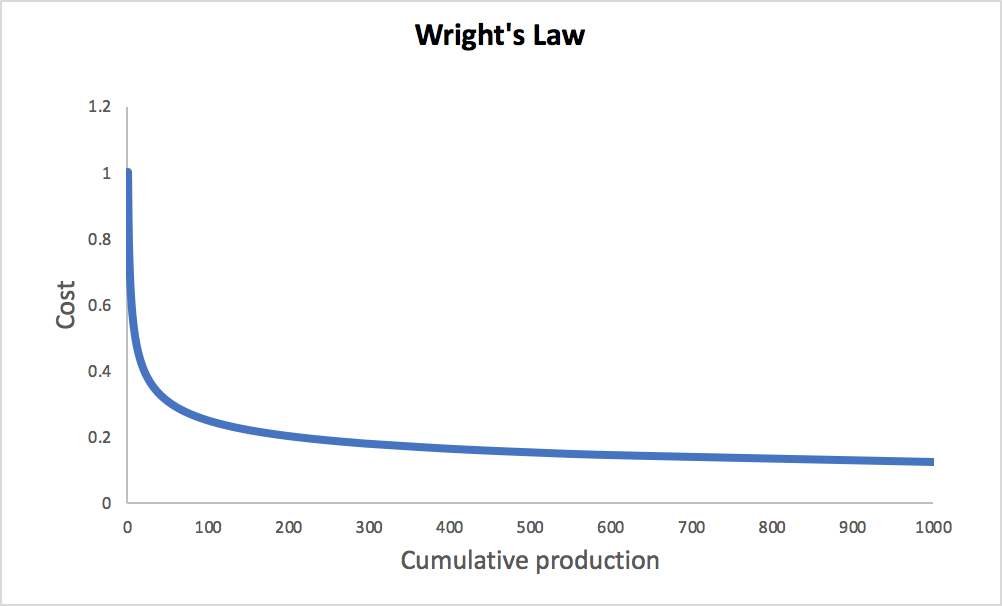

Rampant growth of solar capacity is ultimately the product of Wright’s Law—a framework that illustrates the exponential growth of technology. When solar modules were first created, they were developed by the government specifically for use in remote energy generation on satellites. Solar module production at that time was extremely costly and, subsequently, production was few. Though, as new uses for solar energy were developed and solar began to be seen as a terrestrial solution for greenhouse gas emission, production responded to the demand. With standardization of production processes and decreasing input costs, solar module prices began to fall.

This is a positive feedback cycle. Nevertheless, for this cycle to begin, there needs to be a catalyst in the form of an investment. In the case of solar, this was the legislation that created incentives for firms to invest in photovoltaic modules. Renewable Production Standards, tax credits, net-metering, SRECS, and many other policy mechanisms have been the wind under solar’s wings.

The frenzy doesn’t appear like it’s stopping anytime soon, either. As costs of solar energy are projected to continue falling, demand for solar is only likely to increase. Not to mention, in 2022 the federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC) will provide a 26% discount to anyone seeking to install residential solar modules. The U.S. Energy Information Administration states that “solar power and batteries account for 60% of the planned new U.S. electrical generation capacity.”

The ball is rolling for solar energy as we continue deploying record-breaking capacities. This production goes to show that state and federal legislation targeted at increasing solar capacity are working. The future is literally and figuratively bright for solar.

We Now Face the Good Problems of Solar Energy—Policy’s next problem is recycling millions of expired solar panels.

The last decade’s massive roll-out of solar technology is the reflection of a collective anxiety about the ongoing environmental crisis. We seek to throw-out fossil fuels because they are non-renewable, creating a by-product called CO2 which poses a major externality on the environment through climate change—a sliver of scientific knowledge that is known, and increasingly accepted, by absolutely everyone. Solar is alluring because it is renewable, posing no obvious environmental threat like greenhouse gasses. To many, renewable energy holds the promise of an idealistic, closed-loop economy where no waste is generated, products are built to last, and humans have a mutualistic relationship with the natural world.

Nevertheless, no source of “renewable energy” is completely renewable. Solar panels, like everything else, must succumb to the laws of Thermodynamics and depreciate. When a solar panel is no longer in operation, what’s left behind is a hunk of silicon, plastic, and silver that—as of now—we throw into a landfill. One major mistake when assessing the cleanliness of a technology is only considering its environmental impact while it’s in use. Environmental impacts should consider the entire life cycle—that means the impacts of making the technology and the impact it makes after its use. While the active time of solar panels is extremely beneficial, the production process and end-of-life stages of solar technology tell a different story.

Producing solar panels is a generally wasteful process. Manufacturing the technology requires machining holes through silicon wafers, creating a by-product called “kerf” which is a mix of highly-valuable, ultra-pure silicon and sawing fluid. Because extracting the silicon from the mixture is extremely expensive, solar manufacturers often consider it waste. According to the French start-up ROSI, “with the current solar capacity (115 GW worldwide), the photovoltaic module production is creating about 200,000 tons [$1.5 billion] of photovoltaic-grade silicon “waste” through kerf.” Ideally, the silicon that accumulates as kerf could be reintegrated into the production processes, but no manufacturers are doing this at the moment.

No manufacturers seem to have solved the end-of-life (EoL) dilemma of expired solar modules, either. As of now, only 10% of solar panels are recycled. Because the average lifespan of a solar panel is only around 30 years, the millions of solar modules deployed over the last two decades are set to come offline and into a landfill in the next decade. After that there is an unprecedented pipeline of expired solar technology to come as a product of our current era of deployment. By 2050, $2 billion worth of materials from solar panels are set to be dismounted and we have no large-scale end-of-life solution to account for it.

Ultimately, the wastefulness of the solar industry will pose a major externality on society. By discarding billions of dollars worth of ultra-pure materials, we are declining the opportunity to reduce natural resource extraction—a process that can be extremely threatening to local communities and will require an exorbitant amount of fossil fuels. Discarded solar panels cause additional environmental threats because they contain heavy metals such as cadmium and lead. Not to mention, the United States is already facing a waste crisis, as landfill space continues to dwindle at a remarkable rate.

Businesses, too, are losing out on billions of dollars of input materials and operating in a model that doesn’t maximize their long term profitability. The major material and monetary waste of the solar industry is the skeleton in the closet of what would otherwise be an incredible start to the sustainable energy infrastructure.

Hidden in this precarious dilemma, though, is an opportunity to recoup billions of dollars worth of materials and create a sustainable solar industry. Solar developers and policymakers know that solar modules only last a few decades and they know we have no way of dealing with them. The standard contract for solar developers—the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA)—usually stipulates a 25 to 30 year contract term for this very reason.

What are we waiting for?

Recycling solar panels requires processes that are still developing and are currently not cost effective on a commercial scale. Each module is like a sandwich with a plastic shell that allows for sunlight to pass through, but protects its complex amalgamation of silicon and silver components from the elements. The complex construction of the modules makes deconstructing them very difficult. Start-ups such as ROSI and Veolia are developing processes to recycle solar panels through various processes. The current, most popular method is creating a “glass cullet” (a mixture of ground up silicon, plastic, and glass) which is sold as a construction material. Unfortunately, glass cullet is cheap—selling for around $3 a panel—making it an unprofitable end-of-life solution for solar developers.

A more profitable solution would be removing and reselling the valuable internal components such as silicon and silver threading. While ROSI has begun using an innovative chemical-bath process to retrieve these materials, they and many other start-ups are still in preliminary stages of development. Ultimately, solar recycling processes and technology are still in the infant stages of Wright’s Law—low production at high marginal costs. Solar developing firms cannot reasonably be expected to recycle in a profitable way at this point in time.

Policymakers haven’t drafted very much legislation on the issue either—and their uncertainty about recycling technology is very much reflected in recently proposed policies. While there are no federal regulations driving the industry, many states have created commissions to investigate and make recommendations on end-of-life options for solar. Last year, three bills were proposed in California, Hawaii, and Rhode Island proposing best practices for solar recycling. The Hawaii bill considers adopting a fee for the disposal of solar modules into landfills—a financial incentive that could stimulate the industry. If passed, these bills would join a patchwork of legislation in Washington, New Jersey, and North Carolina. Many of the state investigations will generate guidelines by this summer, but none have made firm resolutions about requiring specific recycling standards any time soon. It seems as though policymakers know solar recycling will be an issue, but don’t know how—or if—they should deal with it.

The absence of policy around solar recycling makes sense. Up until very recently, no policymakers would consider a bill that would raise the marginal cost of producing solar. The goal is and has been making solar energy as attractive as possible. And, obviously, the process of establishing a renewable energy infrastructure begins with a large-scale rollout of solar technology. At some point, though, financial incentives targeted specifically at growing solar energy will end. Indeed, questions about the advantages of certain solar incentives are beginning to arise. In California, legislators are beginning to roll-back certain rooftop solar incentives because they believe it causes unequal electricity price increases for households that aren’t equipped with solar. Others are warning of residential solar incentives being withdrawn in the next 5 years.

When the policymakers are comfortable pulling the brakes on incentives targeted at stimulating mass solar deployment, their focus needs to turn to creating necessary support systems for the renewable energy infrastructure. Namely, developing policies with incentives to stimulate technological growth in the solar module recycling industry. This may mean implementing fees to discard solar panels in landfills as is being considered in Hawaii.

Because the technology and process of recycling is so costly, the industry needs to be stimulated by policy in the same way that the government incentives for solar production stimulated production of those technologies—thus increasing demand, production, and subsequently prices. As stated before a technology cannot scale unless there is an initial investment that begins the price reduction process explained by Wright’s Law. After a certain amount of growth in the industry, choosing to recycle solar panels—and recoup the millions of dollars worth of usable resources—may eventually be financially feasible, and even beneficial, for solar developers. Sustainable business is no longer an oxymoron. With the right incentives, businesses will elect to recycle so they can maximize their profitability—just as they now race to generate solar energy.

Obviously, there is no malevolence in deploying solar energy modules. These are the considerations of an adolescent period in renewable energy. Rapid deployment of solar technology is important, but it’s not the only consideration that must be made. If we want a truly sustainable energy infrastructure, we need to look at the big picture—we need to think in the long run. Regulatory bodies need to be thinking of policies to stimulate end-of-life solutions for solar energy. This is the path towards a closed-loop, genuinely sustainable energy infrastructure.

References

“Op-Ed: Sorry, Rooftop Solar Supporters, California Incentives Really Do Punish the Poor.” Los Angeles Times, 28 Mar. 2022, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2022-03-28/solar-rooftop-net-energy-metering-incentives-california-public-utilities-commission-cpuc-gavin-newsom.

Kerf Recycling | ROSI. https://www.rosi-solar.com/kerf-recycling/. Accessed 8 Apr. 2022.

Prieto-Sandoval, Vanessa, et al. “Towards a Consensus on the Circular Economy.” Journal of Cleaner Production, vol. 179, Apr. 2018, pp. 605–15. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.224.

“Real Estate Company Partners with Safari Energy to Develop Solar Portfolio.” Solar Power World, 22 Nov. 2021, https://www.solarpowerworldonline.com/2021/11/real-estate-company-partners-with-safari-energy-to-develop-solar-portfolio/.

“ROSI Solar – Towards Circular Economy in the Photovoltaic Industry.” ROSI, https://www.rosi-solar.com/. Accessed 4 Apr. 2022.

Sihvonen, Siru, and Tuomas Ritola. “Conceptualizing ReX for Aggregating End-of-Life Strategies in Product Development.” Procedia CIRP, vol. 29, Jan. 2015, pp. 639–44.

ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procir.2015.01.026.

“Solar Panels Are a Pain to Recycle. These Companies Are Trying to Fix That.” MIT Technology Review, https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/08/19/1032215/solar-panels-recycling/. Accessed 4 Apr. 2022.

“Solar PV Module Prices.” Our World in Data, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/solar-pv-prices. Accessed 4 Apr. 2022.

State Renewable Portfolio Standards and Goals. https://www.ncsl.org/research/energy/renewable-portfolio-standards.aspx. Accessed 5 Apr. 2022.

“Time Is Running Out: The U.S. Landfill Capacity Crisis > SWEEP.” SWEEP, 4 May 2018, https://sweepstandard.org/time-is-running-out-the-u-s-landfill-capacity-crisis/.